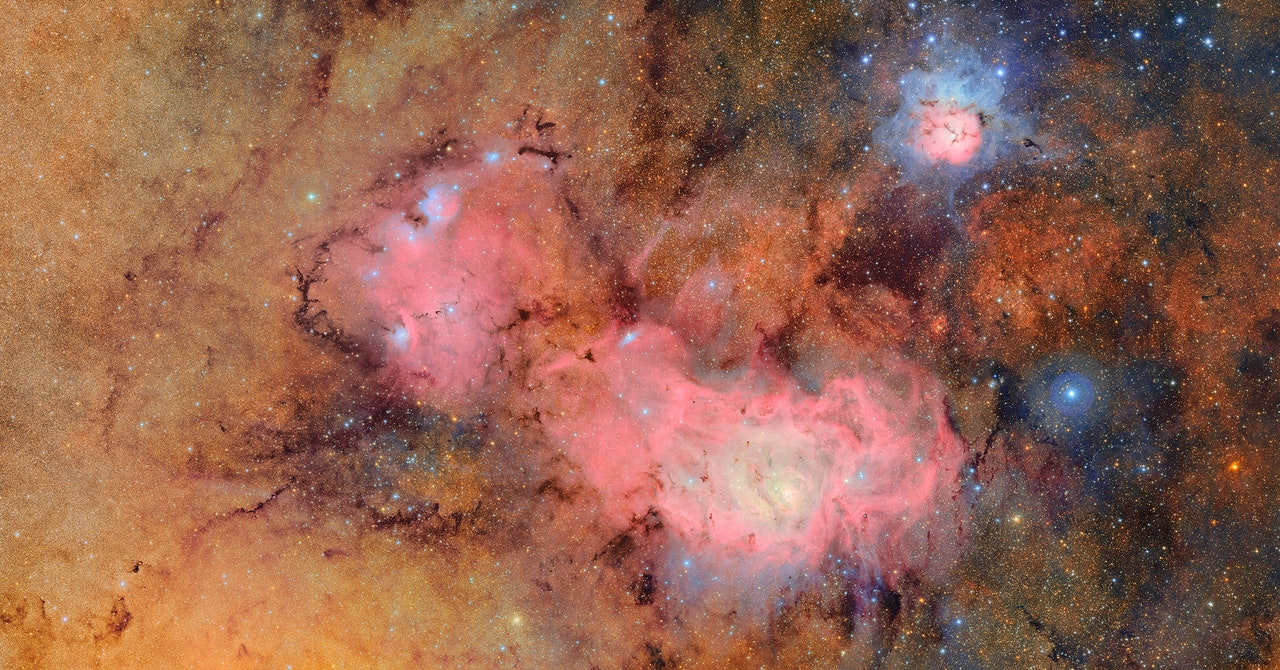

In the past couple decades, astronomers have come to realize that our solar system is something of an oddball. Many other systems have large gas planets orbiting close to their stars with the smaller rocky planets farther out, the opposite of what we see around the sun.

“We know that planets in the solar system did not start out at their current positions,” Juric says. Neptune used to be twice as close to the sun, and the other gas giants began their lives closer in as well. Jupiter may have even tossed another gas giant out of the solar system entirely.

“All of this happened early in the solar system, and we’d like to know how and when,” Juric says. Using information contained in the solar system’s ancient fragments—the positions, trajectories, shapes, and sizes of millions of asteroids, comets, and other small bodies—astronomers can write a new history of our planetary system. “We tend not to be interested in any particular one, but when you find 5 million, they tell you a lot about what happened.”

Some asteroids among the millions, however, are bound to capture particular interest. A handful won’t be part of the solar system’s history at all, but rather visitors from other planetary systems, ejected from their home stars to fly, by chance, through our cosmic neighborhood. Only two such objects have been discovered so far, and one, called ‘Oumuamua, looks nothing like anything seen before.

“This is as close as it gets to actually visiting another stellar system and looking at the planets and at the components that went into the planets,” Juric says. Rubin is expected to find anywhere between 10 and 120 of these exotic interlopers. “If there’s an interstellar object passing by, and it just happens to be in the right trajectory, you can launch [a spacecraft] to intercept it. Now that would be amazing.”

Rubin will also double the number of known potentially hazardous asteroids larger than 140 meters across—big enough to cause regional devastation or disastrous tsunamis if one hit Earth—from about 40 percent to 80 percent.

Perhaps the most exciting discovery Rubin could make in the solar system is confirming or ruling out the existence of Planet Nine. This hypothesized planet, between five and 10 times the mass of Earth, may be lurking in the outer reaches beyond Neptune, its presence betrayed by an unusual clustering of small objects out there, known as trans-Neptunian objects, which appear to have been nudged into place by an unseen world.

If Planet Nine exists, the Rubin science team believes there is a 70 to 80 percent chance that it will be in a position where the telescope can detect it directly. If it is somewhere harder to see, such as in the foreground of the Milky Way’s bright galactic plane, the team is still confident that they could detect the planet’s presence indirectly.

“We will find so many trans-Neptunian objects, through which Planet Nine has been inferred to exist, that we would almost certainly answer the question of whether that signal folks are seeing right now is real,” Juric says. “We either find it directly or we find extremely strong circumstantial evidence that it’s there or not there.”