The company’s other cofounder is Eriona Hysolli, previously the head of biological sciences at Colossal Biosciences, which earlier this year claimed to have brought back extinct dire wolves by editing the embryos of modern-day gray wolves.

Manhattan Genomics’ scientific contributors—so called because they will take a more hands-on role than traditional biotech advisers—include New York-based IVF doctor Norbert Gleicher and data scientist Stephen Turner, previously the head of genomics strategy at Colossal Biosciences, where he sequenced embryos before and after gene editing and analyzed off-target effects. Carol Hanna and Jon Hennebold, researchers at the Oregon National Primate Research Center at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), are providing expertise on primate embryology. A scientist who has conducted gene-editing work on human embryos was originally included among the list of scientific contributors, but when contacted by WIRED he said he was not officially working with the company.

John Quain is advising the company on ethics. Quain, a technology writer and a fellow in the bioethics program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, gave a talk at a philosophy event last year titled “Drawing the Germline: Why Moratoriums on Human Heritable Genetic Engineering Should Be Lifted.”

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a biologist at OHSU, is consulting with the company on human embryo research. Mitalipov is known for developing a “three-parent baby” technique that involves removing the nucleus of a human egg and placing it into another. (Mitalipov did not respond to an interview request from WIRED).

In what Tie sees as a sign of growing interest in human embryo editing, she says the company received more than 150 applications from qualified scientists in the first 24 hours of posting a role for a genome engineer.

She did not specify what genes Manhattan Genomics will target first, but says the company will focus on ones that have the strongest correlation with disease and are the simplest to go after, such as those that cause Huntington’s disease, cystic fibrosis, and sickle cell anemia—known as monogenic disorders because they are caused by mutations in a single gene.

Since He’s experiments in 2018, scientists have honed newer, more precise forms of Crispr, which Tie plans to test and compare for safety and efficacy. She says the company will start with studies in mice then move to monkeys. Human trials are still many years off and would likely face regulatory obstacles in the US. A congressional rider bans the Food and Drug Administration from considering trials involving intentionally modified human embryos that are used to start a pregnancy.

“We are obviously at a very early stage, and it will take significant work in collaboration with the FDA to get to a practical clinical application,” Gleicher tells WIRED. “But I am optimistic that for carefully selected indications, it should be doable within a reasonable time frame.”

At least initially, Gleicher sees embryo editing being used in cases where an IVF patient has only a few embryos to work with and all of them are affected by a single-gene disease. Age is a major factor in the number of eggs, and thus embryos, an IVF patient is able to produce, so Gleicher says older patients may especially benefit. “This is, indeed, what attracted me to the project,” he says.

Gleicher’s New York-based clinic, the Center for Human Reproduction, serves a large population of patients over the age of 40. He says his patients frequently ask why it’s not yet possible to “improve” or “fix” embryos.

Turner got involved with the company through Hysolli, his colleague from Colossal, but says he wasn’t immediately supportive of Manhattan Genomics’ vision. “Embryo editing raises serious ethical and scientific questions. I agreed to get involved because I want to see this work, if it proceeds at all, done transparently, under independent oversight, and focused on preventing severe disease,” he says, adding that if those conditions aren’t met, he will no longer be involved.

Even if the company manages to show that embryo editing can be done safely, there may be few use cases for it—at least in terms of preventing serious inherited diseases.

“For mutations that are inherited, in the vast majority of cases they can be addressed by embryo screening rather than embryo editing,” says Kiran Musunuru, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania who is developing gene-editing treatments.

A type of testing used in IVF called preimplantation genetic diagnosis can evaluate embryos for specific inherited genetic diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, or Tay-Sachs. “There are very rare cases where no healthy embryos are possible, like when the two parents both have cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease,” Musunuru says. In those cases, he says donated healthy sperm or eggs could be used instead.

He also points to the fact that many genetic diseases are caused by spontaneous mutations that are not inherited from their parents. These “de novo” mutations are difficult to detect with preimplantation genetic diagnosis, and Musunuru says in those cases, gene-editing treatments would have to be given at the fetal stage or after birth. Musunuru was part of a team that created a custom Crispr treatment for an infant with a rare and often fatal metabolic disease.

Fyodor Urnov, a professor of molecular therapeutics at UC Berkeley and a scientific director at its Innovative Genomics Institute, says he worries that the interest in human embryo editing for reproductive purposes is driven by a “quasi-eugenics” mindset, rather than a true desire to fix genetic disease. “Why is money being poured into this? Because at the end of the day, those who have money want to ‘improve’ their babies,” he says.

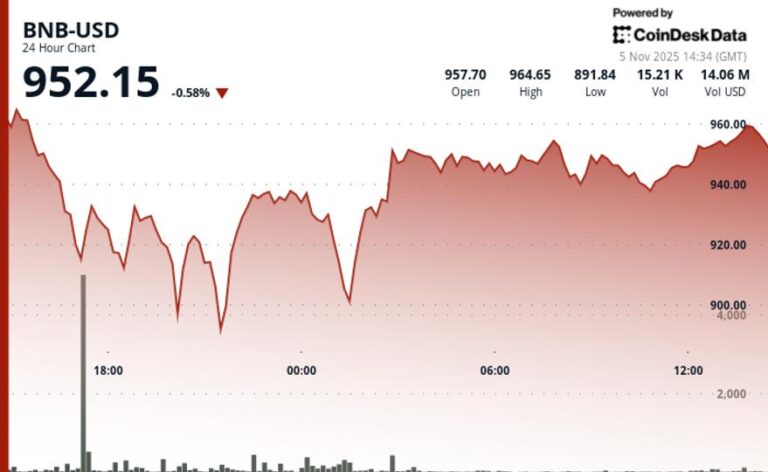

At least one other company, Bootstrap Bio, is also seeking funding for human embryo editing. And in June, Coinbase CEO and billionaire Brian Armstrong posted on X that he was ready to invest in an embryo editing company. “I think the time is right for the defining company in the US to be built in this area, approaching it in a scientifically rigorous way, solving an unmet need,” he wrote. Manhattan Genomics has not disclosed its investors or how much it has raised, though Tie says Armstrong is not an investor.

Jeffrey Kahn, director of the Berman Institute of Bioethics at Johns Hopkins University, says he has concerns about heritable gene editing bypassing the typical route of academic research and being taken up by tech startups.

“Research might be slower or less efficient in academia, but it requires institutional oversight and the restrictions that come with government funds,” he says. Kahn served on an international commission convened by the US National Academy of Medicine, the US National Academy of Sciences, and the UK’s Royal Society from 2019 to 2020 to assess the potential clinical applications of heritable human genome editing. In a report released in September 2020, the commission recommended that gene-edited human embryos should not be used to create a pregnancy until scientists can establish that precise genomic changes can be made reliably without introducing undesired changes.

The committee did not propose an outright ban on human embryo editing but recommended proceeding cautiously and incrementally. It said that countries should have extensive societal dialogue before determining whether to permit its use. And even then, the technique should first be used only for those couples who have little or no chance of having a genetically related baby that does not inherit a serious monogenic condition—such as in the extremely rare case of a parent that carries two mutations for Huntington’s disease. Humans carry two copies of each gene, and each parent passes one of them on to their children. As only one copy of a mutated gene is needed to cause Huntington’s, one parent with two copies would pass on the disease to all embryos.

“When we were working on that report, I think we all thought this research would live in the academic environment, and so the rules would apply. But when you’re outside of that environment in a startup, the question of how do we make sure this happens responsibly becomes much more important,” Kahn says.

Tie says the company plans to follow the recommendations laid out in the commission’s report.

Just this year, the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy, and the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy called for a 10-year moratorium on heritable gene editing, warning that it “remains far too risky and ethically fraught for clinical use.”

Tie maintains that human embryo editing is a valid route to explore. She says after announcing the company in August, dozens of people with genetic diseases in their families reached out to express their support. “Even though it’s not going to be used in the clinic right away,” she says, “it is still worthwhile to fight to get this to be evaluated seriously by regulators.”